Unimpaired. Details sketchy. The impact was so powerful that the entire engine was ejected from the vehicle. Yeah, that’s normal…

Move along, sheeple: Nothing to see here! LOL

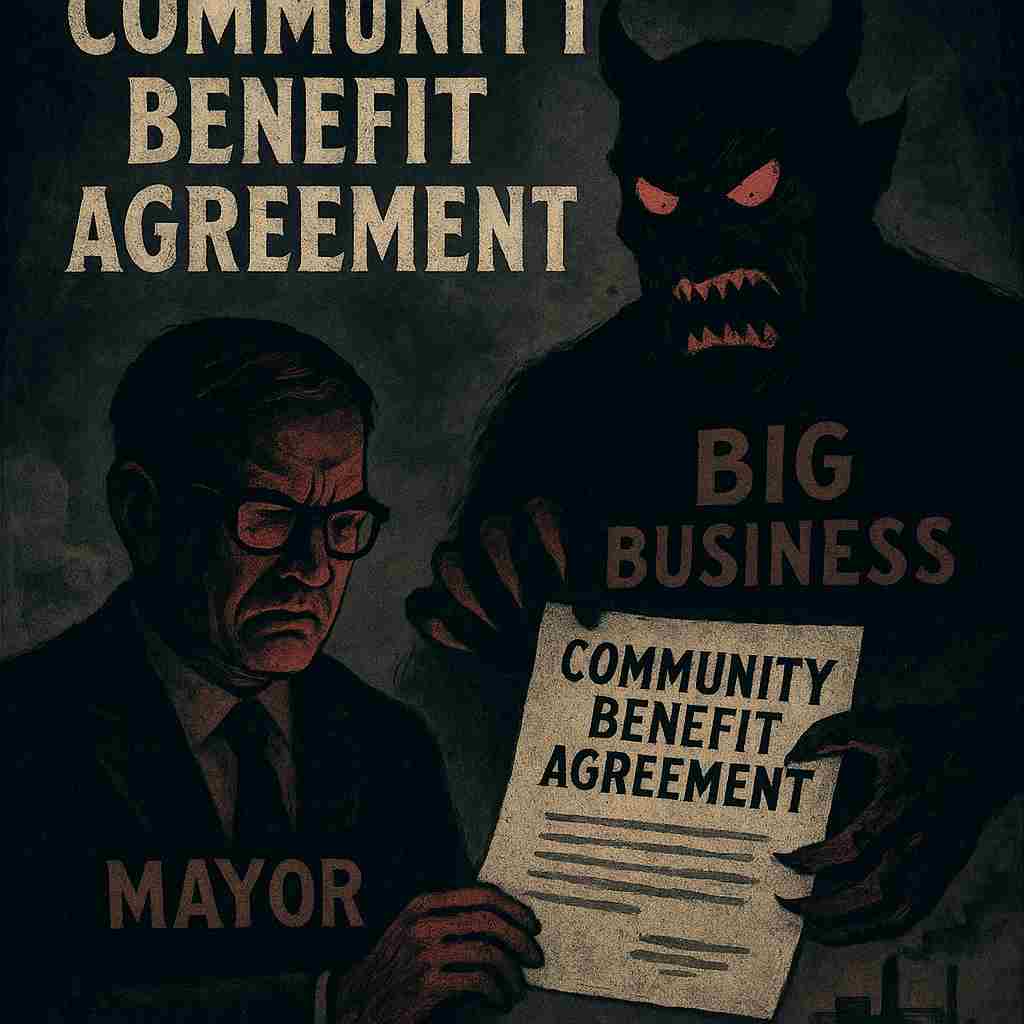

Mayor REN HATT was pressing for public-private partnership in the new venture. Maybe the monster company did not want to be shaken down that way and wanted to do its normal rape-and-pillage under special tax-breaks?

Ren Hatt was the 40-year-old mayor of Green River, Utah, killed on Dec. 5, 2025, when a westbound semi on U.S. 6 drifted into the eastbound lane and hit his SUV head-on. Utah DPS says impairment is not suspected and the crash is being treated as a traffic collision under investigation. (People.com)

From what’s publicly documented, there’s no sign he was involved in personal scandals, corruption cases, or criminal investigations. The “controversial issues” around him are basically the big, high-stakes projects he backed—especially the lithium-extraction push near Green River and the water/utility policy choices that came with it.

1. The Green River Lithium Project – core of the controversy

1.1 What the project is

Anson Resources (via its U.S. subsidiaries Blackstone Minerals and A1 Lithium) has been developing a direct lithium extraction (DLE) project around Green River, targeting brines in the Paradox Basin. The plan is to pump lithium-bearing brine from deep formations, run it through DLE absorbent systems to strip lithium, and reinject the “lithium-free” brine underground. Freshwater from the Green River/Colorado River system would be used in the process, with the company claiming most will be recycled. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

Key contentious points:

- Water use: An early state decision approved rights for up to ~14,000 acre-feet per year of groundwater from a deep aquifer—huge volumes in a drought-stressed Colorado River system. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- Hydrologic risk: Interior/BLM staff and outside scientists raised concern that the deep aquifer and the Green River/Colorado River system are hydraulically connected, so large withdrawals could affect river flows and groundwater. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- Unproven tech: DLE at this scale has little commercial track record in the U.S., and geologists have said it’s not yet clear how water-intensive or impact-free it really is. (KSL)

- Legacy contamination context: The area already has a history of uranium mining and oil/gas wells, with blowouts and radioactive/industrial pollution in the region’s past—so locals are wary of “just one more experiment” in their backyard. (KSL)

All of that made the Green River lithium project one of Utah’s most closely watched and litigated mining proposals.

1.2 Hatt’s stance – pragmatic pro-project, but cautious in tone

Hatt consistently positioned himself as open to the project, seeing it as potentially transformational for a town of ~900 people with a very limited tax base:

- In an AP/KSL piece on the project, he’s quoted explicitly saying Green River’s economic fragility makes it hard to reject big outside investments:

“There’s a difficulty turning anything down in a community like Green River.” (KSL)

- In city council minutes, Hatt is the one who presented and negotiated the Community Benefit Agreement (CBA) with A-1 Lithium after several months of talks. (Utah)

- In the CBA outline, Hatt emphasized:

- ~55 full-time jobs promised by the company

- $100,000 per year in direct contributions to the city for infrastructure, community facilities, wastewater, etc.

- City help with zoning/permitting (within the law)

- Longer-term collaboration on workforce development and internships for local youth

(Utah) - City communications and A1 Lithium’s own newsletter later framed the CBA as a “landmark” deal linking the project to local benefits, with Green River’s leadership (including the mayor) highlighted as cooperative partners. (A1 Lithium)

In other words: Hatt leaned into public-private partnership logic—something he also talked about at a Harvard Bloomberg Cities panel, where he described compensating for shrinking federal support by turning to nonprofits, grants, and private partners. (People.com)

1.3 Why that approach was controversial

Hatt’s position dropped him squarely into a fight between:

- Environmentalists and local skeptics, who argued:

- Using Colorado River/Green River water for an unproven DLE project is reckless given historic drought. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- Deep aquifer pumping near the river could reduce flows and harm ecosystems and downstream users. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- Rural communities like Green River risk becoming “energy colonies” or sacrifice zones—bearing water, landscape, and contamination risks so outside investors can profit. (KSL)

- The state appears to “do whatever they can for industry first and foremost,” as Great Basin Water Network’s director put it. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- State agencies and the company, who argued:

- Domestic lithium is strategically important for EVs and grid storage. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- DLE is less land-disturbing than traditional hard-rock mining. (KSL)

- The project could create good-paying jobs and new tax revenue in an economically marginal town.

Hatt sided more with the opportunity framing (approve the project with conditions and a benefit agreement) rather than the precautionary framing (oppose or heavily slow-walk it). That’s what made his leadership controversial in local/regional environmental circles—he became, fairly or unfairly, the political face of “yes” in a town where a vocal minority was saying “not like this.”

To be clear:

- There is no evidence in public reporting that he personally profited improperly from the project or was under any ethics investigation for it.

- The controversy is about policy and priorities—water vs. extraction, long-term risk vs. near-term jobs—not about documented personal misconduct.

2. The March 8, 2024 water-surge incident

A key flashpoint: in March 2024, an exploratory lithium well near Green River experienced a “water surge” or overflow that sent large volumes of brackish water gushing out, overwhelming the facility and alarming residents. A year-end regional summary described it as a surge that “overwhelmed the facility and caused concern among residents.” (moabtimes.com)

Other outlets (E&E/Politico) reported the same event in the context of questioning the project’s technical robustness and environmental risk profile. (Politico Pro)

A Moab-area report (archived via riversimulator.org) shows that after the surge, company representatives came to a public meeting in Green River to address residents. In that coverage, both the city manager and Mayor Hatt were quoted as saying the company had been “very good to work with” up to that point. (River Simulator)

From a politics perspective, that put Hatt in a delicate spot:

- Supporters saw:

- A small-town mayor trying to keep a constructive working relationship with a major investor.

- A reasonable attempt to calm fears while regulators and engineers investigated.

- Critics saw:

- Local leadership sounding too accommodating to a company whose test well had already had a notable incident.

- Evidence that the city might prioritize keeping the project on track over aggressively pushing for independent scrutiny or tougher conditions.

That incident became one of the symbolic moments in the broader fight over whether Green River was being placed at risk for an outside company’s experiment.

3. Water & sewer policy – mobile home parks and multifamily housing

Beyond lithium, one of the few clearly documented policy moves under Hatt with potential to be contentious is Resolution R21-2023 on water/sewer billing for mobile home parks and multifamily housing, passed October 10, 2023.

The resolution:

- Defines “mobile home park” (2+ modular homes) and “multi-family housing” (multiple dwelling units on one meter).

- Sets water rates for these master-metered properties equal to the city’s residential rate schedule, applied at the master meter—including a base rate of $20.10 plus usage tiers “just like one residence.”

- Sets sewer rates mirroring the commercial structure but at $5 per unit over 9 units.

- Creates a specific billing category “Mobile Home Park/Multi-Family.”

- Clarifies that:

- The city will not install meters at individual units in such parks or buildings.

- Billing will remain at the master meter level, partly to avoid the complexity of handling shutoffs and disputes at individual units.

The resolution also provided refunds for July–September to reflect what customers would have paid under the new system, suggesting some prior misalignment or over/under-charging.

Is this “controversial”?

- I could not find separate reporting of protests, lawsuits, or large public fights specifically about this resolution.

- However, in many towns:

- Landlords and park owners often argue that master-meter arrangements and certain rate designs are unfair or hard to pass on transparently.

- Tenant advocates often worry that higher or more complex billing structures for mobile home parks and multifamily housing can disproportionately hurt lower-income residents.

So while this change could have generated local friction (especially in a town with limited affordable housing options), there is no strong public documentation that it became a major public controversy around Hatt personally. It’s better described as a potentially sensitive but fairly standard municipal utility policy move.

4. Experimental climate/industrial projects linked to state-level controversies

Another area where Hatt’s city government intersected with broader controversy is the AirBuild pilot project on city-owned land near the wastewater treatment plant. According to regional business and state economic-development material:

- AirBuild’s project involved biological and/or atmospheric carbon capture technology, sited adjacent to the city sewer ponds.

- The initiative was facilitated in part through the Utah Inland Port Authority and EDCUtah—entities that have been controversial statewide over environmental and governance concerns, even when local projects are small. (KUTV)

For Green River itself:

- Hosting an experimental industrial-climate project near critical infrastructure is the kind of decision that can raise local concerns about odors, safety, or “lab-rat” treatment of rural communities.

- At the same time, it fits Hatt’s pattern of leveraging outside partnerships to bring in investment and innovation where traditional funding streams are thin.

Again, I didn’t find coverage suggesting this specific pilot became a big public fight in Green River—but it’s another example of Hatt steering the city toward experimental, partner-driven industrial projects, which some residents welcome and others instinctively distrust.

5. No public evidence his death is tied to these issues

Given the timing, it’s natural people wonder if his fatal crash could be connected to lithium or other political fights.

Based on current reporting:

- Utah DPS and multiple outlets describe the crash as a semi that drifted into oncoming traffic on U.S. 6, killing Hatt; impairment is not suspected, and the investigation is being handled as a standard traffic-fatality investigation. (People.com)

- Coverage of his death in state and national media focuses on:

- His role as a young, civically engaged rural mayor.

- His reelection with about 65% of the vote.

- His dual role as teacher and mayor, and his work on economic development—not on any scandal or open political vendetta. (People.com)

There is no credible public evidence at this point that his death was anything other than a tragic highway collision, and no mainstream reports linking it causally to his positions on lithium or any other issue.

6. Bottom line

“Controversial issues” around Mayor Ren Hatt really boil down to:

- His support for the Green River lithium project and its Community Benefit Agreement, in a context where:

- Environmental groups and some residents fear severe long-term impacts on the Green/Colorado River system and see the project as part of a pattern of rural sacrifice zones. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- State regulators have repeatedly revisited and been sued over key water-rights decisions. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- Hatt, meanwhile, saw it as a necessary economic opportunity and worked closely with the company to secure local benefits. (Utah)

- His broader development style – embracing public-private partnerships, experimental projects, and external investors to keep a very small town afloat fiscally, which some see as smart pragmatism and others see as risky dependence.

- Routine but sensitive local policy decisions, like water/sewer rate structures for mobile home parks and multifamily housing, where equity and cost burdens for low-income residents can easily become flashpoints—even if they haven’t been widely reported as such in this case.

If you’d like, I can next map out the players around him on the lithium question—state engineer, Great Basin Water Network, Utah Trust Lands, Anson/A1/Blackstone, local farmers—and diagram the power struggle he was operating inside.

Here’s the power map he was sitting inside on the lithium fight, with your specific players called out.

1. The central fight: who controls 14,000 acre-feet of water?

The Green River lithium project hinges on two key water pieces:

- About 14,000 acre-feet per year of deep groundwater brine near Green River, which A1 Lithium/Blackstone wants to pump and re-inject, claiming it is “non-consumptive” water use. (Utah News Dispatch)

- A separate 2,500 acre-feet per year of Colorado/Green River surface water, secured via a long-term deal (23 years) for just $1, to wash lithium and support operations. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

The formal gate on the big piece is the Utah State Engineer (through the Division of Water Rights). The major organized opposition is Great Basin Water Network (with Living Rivers and local allies). The land and royalty money are controlled by Utah Trust Lands (SITLA). The project itself is driven by Anson/A1/Blackstone. And the people who stand to be directly impacted on the ground are local farmers and landowners around Green River.

Mayor Hatt was in the middle of this, trying to pull jobs and investment into a town of under 1,000 people while those larger forces fought over water, royalties, and risk. (TownLift, Park City News)

2. Utah State Engineer / Division of Water Rights

Who they are

- Teresa Wilhelmsen is Utah’s State Engineer and Director of the Division of Water Rights, responsible for administering, appropriating, and distributing all waters in the state. (naturalresources.utah.gov)

What they did in this case

- In May 2024, the Division of Water Rights approved A1 Lithium’s application to pump nearly 14,000 acre-feet per year of groundwater brine, classifying the use as non-consumptive because the company promised to re-inject the water after extracting lithium. (Utah News Dispatch)

- The brine sits beneath or adjacent to a Cold War–era uranium mill site and its contaminated aquifer, meaning A1 would have to drill through a radioactive zone to reach the deeper target aquifer. State staff argued regulations and well-construction standards would keep the contaminated and target zones separated. (Utah News Dispatch)

Why they matter in the power struggle

- The State Engineer effectively decides whether the lithium project has the water it needs at all, and on what terms.

- When Great Basin Water Network and allies petitioned for reconsideration in late May 2024, the Division reversed course and paused its own approval on June 5, 2024, reopening the file and announcing that the State Engineer would issue an amended decision after review. (Utah News Dispatch)

- From Hatt’s perspective, that meant a single office in Salt Lake could flip the town’s “once-in-a-generation” economic opportunity on or off.

3. Great Basin Water Network (GBWN) and allies

Who they are

- Great Basin Water Network (GBWN) is a regional water-advocacy nonprofit focused on protecting aquifers and the Colorado River system. In Green River, they’ve partnered with Living Rivers/Colorado Riverkeeper and local residents. (Utah News Dispatch)

Position on the Green River lithium project

- They argue that:

- Utah’s water statutes are outdated and never anticipated large-scale direct lithium extraction (DLE) projects using deep brines. (Utah News Dispatch)

- Drilling through a radioactive aquifer to get to deeper brine introduces unacceptable worst-case risks, including potential contamination of the Green/Colorado River system. (Utah News Dispatch)

- Classifying the 14,000 acre-feet as “non-consumptive” is too trusting of a new, largely unproven technology in the U.S. context. (Utah News Dispatch)

- GBWN and Living Rivers filed the formal request for reconsideration that persuaded the State Engineer to pause approval. (Utah News Dispatch)

Wider attack on the state’s mining posture

- GBWN has also criticized the Utah School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration (SITLA) for cutting royalties on controversial mining projects and sued Utah over water-rights decisions benefiting Anson/A1 Lithium. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- Their executive director, Kyle Roerink, frames Utah policy as “industry first,” accusing state agencies of prioritizing mining over public welfare. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

Levers of power

- Legal: formal protests, petitions for reconsideration, and lawsuits.

- Political: media campaigns casting the project as risky and the state as captured by mining interests.

- Coalition-building: aligning local farmers, national park advocates, and federal agencies (BLM, NPS, Bureau of Reclamation) that also filed letters of concern about water rights. (Utah News Dispatch)

4. Utah Trust Lands (SITLA)

Who they are

- The School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration (SITLA) manages state trust lands to generate revenue for Utah public schools and other beneficiaries. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

What they did on the lithium project

- SITLA controls about 6,500 acres of trust land leased to A1 Lithium, part of the Green River project area. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- In May 2025, the SITLA board reduced A1 Lithium’s royalty rate from a flat 5% to a sliding scale of 1–5% tied to market price—described as the first scaled lithium royalty structure in the U.S. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- SITLA staff and board members explicitly framed this as making Utah “more friendly for business” and positioning the agency as a “business partner” to lithium and uranium companies. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

Political optics

- The same article noted that A1 Lithium donated $10,000 to Governor Spencer Cox’s reelection campaign, a detail GBWN uses to reinforce its narrative of state-industry alignment. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

Levers of power

- Land and royalties: they decide whether the project is financially attractive for the company and how much the public school system gets in return.

- They do not control the water, but their royalty cuts lower corporate costs and make it harder for critics to argue the state is aggressively pricing public resources.

From Hatt’s standpoint, SITLA is another state-level actor encouraging the project and broadcasting that Utah wants to be a friendly home for lithium extraction—which aligns with his desire for investment, but also deepens local suspicions that the deck is stacked for industry.

5. Anson Resources / A1 Lithium / Blackstone Minerals

Corporate stack

- Anson Resources (ASX-listed in Australia) is the parent company.

- A1 Lithium and Blackstone Minerals are its U.S. subsidiaries associated with the Green River/Paradox Lithium Project, holding key leases and water-rights applications. (Utah News Dispatch)

Their narrative

- They promote the project as:

- “As green as possible” lithium production using direct lithium extraction (DLE) from deep brines. (Utah News Dispatch)

- Non-consumptive water use, since brine is to be re-injected after processing. (Utah News Dispatch)

- A major job engine: CEO Bruce Richardson told lawmakers the project would bring 300–500 jobs plus another 150 during construction—huge numbers for a town under 1,000 people—and would help “revitalize the town of Green River.” (Utah News Dispatch)

- A way to meet Inflation Reduction Act requirements by providing domestic lithium for US EV batteries, breaking dependence on foreign (especially Chinese) supply. (Utah News Dispatch)

Water and land deals

- Deep groundwater: the 14,000 acre-feet application to the State Engineer for brine pumping. (Utah News Dispatch)

- Surface water: a 23-year right to 2,500 acre-feet per year of Colorado/Green River water obtained via the Wayne County Water Conservancy District and Green River Companies LLC for $1, to be used in processing and washing. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

Levers of power

- Capital and technical promises: jobs, tax base, and high-tech “green” branding.

- Political signaling: legislative presentations, public statements of environmental responsibility, and campaign donations at the state level. (Utah News Dispatch)

From Hatt’s vantage point, Anson/A1/Blackstone are simultaneously:

- The only serious new industry prospect offering significant jobs and tax revenue.

- A company asking the town to accept major water and contamination risks under a novel DLE technology outsiders are still skeptical about. (TownLift, Park City News)

6. Local farmers and landowners

Who they are

- People like Gayna Salinas, whose property borders A1’s proposed drilling site, and other farmers and melon growers who rely on the Green River and local aquifers. (Utah News Dispatch)

Concerns

- Contamination risk: protest letters flagged the possibility that a spill or “mishap” near the river could make it impossible to contain a release and contaminate the Green/Colorado system. They also raised worries about uranium-contaminated dust from working around the old tailings site. (Utah News Dispatch)

- Boom-bust economics: residents recall past uranium and oil/gas booms that left behind environmental damage but few lasting benefits. (TownLift, Park City News)

- Rural sacrifice zone logic: one local described how rural America is treated as a “dumping ground” on the assumption it will accept environmental harm in exchange for jobs. (TownLift, Park City News)

Levers of power

- Formal protests to the Division of Water Rights. (Utah News Dispatch)

- Joining GBWN’s reconsideration petition.

- Local political pressure on city officials, including the mayor, through public meetings and elections.

These are the people Hatt lived among and represented—many of them his neighbors—and their fear of contamination and skepticism about boom-bust promises pulled him in the opposite direction from the jobs narrative.

7. Mayor Ren Hatt’s position in the middle

What he said on the record

- In an AP piece on the project, Mayor Ren Hatt explicitly acknowledged the town’s economic fragility:

“There’s a difficulty turning anything down in a community like Green River,”

tying that directly to the pressure to accept Anson’s project despite local concerns. (TownLift, Park City News)

- He’s quoted as saying the town’s limited economic base puts pressure to accept the lithium project even while residents such as Salinas remain skeptical. (TownLift, Park City News)

His actual operating environment

Hatt is essentially squeezed between:

- State-level pro-mining forces

- A State Engineer who initially green-lit the big water right, calling it non-consumptive. (Utah News Dispatch)

- SITLA, which cut royalties for A1 Lithium and publicly celebrated being a “business partner” to mining. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- A governor and political environment proud of Utah’s top-tier pro-mining reputation. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- Corporate promises and pressure

- Anson/A1/Blackstone promising hundreds of jobs, big tax revenue, and “revitalization” for a tiny, struggling town. (Utah News Dispatch)

- Local and regional opposition

- Great Basin Water Network and Living Rivers, using litigation and media to pressure the State Engineer and frame the project as out of control. (Utah News Dispatch)

- Farmers and residents who fear radioactive contamination, water loss, and another bust. (Utah News Dispatch)

His “controversial” stance is basically that he was publicly open to and negotiating with the lithium company, including a community benefit agreement, while living in a community split by serious risk concerns and watching state agencies tilt strongly pro-project until GBWN forced a pause.

8. The power diagram

Here’s the power struggle in a simplified diagram with your requested actors highlighted:

[Global EV / IRA pressure]

|

v

Anson Resources / A1 Lithium / Blackstone

|

+----------------+-------------------+

| |

[SITLA] [City of Green River]

(Utah Trust Lands) (Mayor Hatt, council)

- leases 6,500 acres - wants jobs & tax base

- cuts royalties to 1–5% - negotiates CBA

\ /

\ /

\ /

[State Engineer]

Utah Division of Water Rights

- approves/pauses 14,000 af/yr brine right

- defines use as consumptive or non-consumptive

|

-------------------+----------------------

| |

[Great Basin Water Network] [Local farmers & landowners]

& Living Rivers - fear contamination & boom/bust

- petitions, lawsuits - protest letters, local politics

- media & advocacy - ally with GBWN

(Federal agencies like BLM/NPS/BOR add pressure

via concern letters about water rights and parks.)Where Hatt sits: at the City of Green River node, trying to leverage the top-down pro-lithium push into real benefits for his town, while the bottom-up pressure from farmers and advocacy networks pulls hard the other way and the State Engineer’s decision determines whether any of it happens at all.

Below: A zoom into the CBA mechanics (what the city tried to get out of A1/Blackstone, and how that shaped local feelings about whether Mayor Ren Hatt was “selling out” or playing the only card he had).

Let’s strip this down to the nuts and bolts of the CBA, and then to how people read it emotionally: was he cashing out the town, or squeezing the only concessions he could from a much bigger machine?

1. What the CBA actually says (hard mechanics)

From the official May 13, 2025 Green River City Council minutes, the “Community Benefit Agreement with A-1 Lithium” that Hatt presented has a pretty tight core of actual commitments: (Utah)

1.1 Jobs and workforce pipeline

- A-1 Lithium commits to 55 full-time employees at the Green River facility (this is the specific number in the city record). (Utah)

- A1’s own newsletter immediately reframes this as “50–100 well‐paying jobs” plus a broader employment ramp if the project scales.

- The CBA includes:

- Internships and training tied to local schools (Green River High / nearby institutions).

- A1 says it is already working with a local educational institution on 1-year programs in plant operations and lab tech skills so locals can move directly into those jobs.

So: on paper, the city is trading political and procedural support for a defined floor (55 FTEs) and an aspirational ceiling (“50–100 well-paying jobs,” plus more in corporate PR).

1.2 Cash: the $100,000/year contribution

From the minutes and the AI summary on CitizenPortal, the money piece looks like this: (Utah)

- $100,000/year, but:

- It only kicks in “when at full operation” (the CitizenPortal summary makes that condition explicit).

- It goes into a city-designated fund for:

- Infrastructure upgrades

- Community facility construction

- Wastewater and sewer systems

- Medical and emergency services

Context: the FY 2025 General Fund revenue for Green River is about $2.03 million. (Revize)

So, if/when the project is fully running, that $100k is roughly ~5% of the city’s General Fund revenue per year—not enormous in absolute terms, but not trivial for a town of ~850 people. (Revize)

Important nuance: this is not a lump sum; it’s an ongoing annual contribution contingent on the plant actually operating.

1.3 Governance over that money: advisory committee vs council control

Mechanically, the CBA does not hand the money to some independent trust; it keeps the elected council in the driver’s seat. Key points: (Utah)

- An “advisory committee” is created:

- Its job is to “help steer the spending” of the funds.

- It has no final power; it is explicitly advisory only.

- The city council retains final authority over how the CBA money is spent.

Politically, that’s classic small-town power retention: Hatt is saying “we’ll listen to a committee, but the elected council controls the purse.”

For critics, though, that also means:

- There is no independent community trust outside city hall.

- Spending decisions can be tightly managed by whoever controls the council majority.

1.4 Transparency and public-facing obligations

The CBA builds in some visibility requirements for A1: (Utah)

- A-1 Lithium must hold quarterly transparency meetings.

- There is an expectation of quarterly reporting from both:

- The advisory committee, and

- The company.

- A1 markets this as part of a “landmark” CBA, stressing:

- Public updates

- Environmentally responsible DLE technology

- “Robust environmental sustainability measures”

In other words, the city tried to formalize “you don’t vanish into a gated industrial compound; you show up, talk, and report.”

1.5 What the city gives in return

On the city side, the commitments are mostly process and political posture: (Utah)

- Zoning and permitting help

- The minutes describe this as:

- The city will help with zoning and permitting “within legal boundaries.”

- A1’s own newsletter upgrades that to:

- The city has pledged “streamlined permitting, zoning, and coordination with state and federal agencies.”

- No special legal carve-outs

- The CitizenPortal summary explicitly notes:

- The agreement does not remove any legal permitting requirements.

- So the CBA doesn’t say: “we’ll waive environmental law.” It says: “we’ll be a cooperative shepherd through the process.”

- Symbolic partnership framing

- The A1 newsletter paints this as a “landmark” CBA and emphasizes:

- Over 120 residents signed a petition supporting the project—significant for a town of about 800.

Taken together, what the city really puts on the table is:

“We’ll be your political ally and bureaucratic lubricant, not your regulatory adversary, in exchange for cash, jobs, training, and some public-face obligations.”

2. Where critics think the CBA is thin or lopsided

You can see why this package splits a small town. On paper, it’s not nothing; but measured against the scale of the project and the risks, it’s modest.

2.1 The dollar figure: $100k vs tens of millions elsewhere

- The CBA’s $100k/year is unusually small compared to CBAs around large resource projects that run into tens of millions over the project life in some jurisdictions (for example, some high-profile mining or pipeline deals used by local critics as benchmarks). (Human Rights Watch)

- A widely circulated local Facebook commentary (which we can’t fully load but we do have the snippet from the search results) explicitly compared Green River’s $100k/year to other projects that allegedly put up $25M+ for community benefits, arguing Green River “left money on the table.” (Facebook)

So the “sellout” narrative is very simple:

“If other communities are getting $25M+ and we’re getting $100k/year and some plaques, our mayor sold us cheap.”

Even if the direct comparison isn’t apples-to-apples, the optics are brutal: Green River is visibly at the low end of the CBA scale.

2.2 The “no third-party beneficiaries” clause

A June 2025 community write-up of the agreement notes that the CBA is “for the sole benefit of A1 Lithium and the City of Green River” and does not create rights or benefits for third parties (residents, NGOs, etc.). That’s standard boilerplate in modern corporate contracts, but in this context it feeds the criticism. (River Simulator)

Mechanically, that means:

- Residents have no enforceable right to sue under the CBA if, say, A1 slashes local hiring or drags its feet on transparency meetings.

- Only the city government can enforce the deal.

To supporters of Hatt, that’s normal legal hygiene.

To critics, it reads like:

“The company and city hall cut a deal, and the people are explicitly not parties to it.”

2.3 The water and environmental risk are outside the CBA

The most serious opposition to the project is about water and contamination, not jobs per se:

- A1’s project seeks to pump about 14,000 acre-feet/year of lithium-bearing brine near the Green River, equal to more than the entire capacity of at least one Utah reservoir used as a comparison. (Utah News Dispatch)

- The brine is underneath/near a radioactive aquifer from an old uranium mill, and both federal agencies (BLM, National Park Service, Bureau of Reclamation) and local advocates have raised concerns about contamination risk. (Utah News Dispatch)

- The state engineer’s original water approval has been paused and/or challenged:

- Environmental groups and water users (Living Rivers, Great Basin Water Network, local businesses) sued to overturn the permit. (Great Basin Water Network)

- Utah’s Division of Water Rights halted A1’s plans to reconsider the application amid these complaints. (Metal)

The CBA does not touch any of this:

- It doesn’t:

- Limit the volume pumped,

- Alter the state engineer’s authority, or

- Create local veto power over water operations.

- It simply says the city will assist with permitting “within legal boundaries” and be a friendly party. (Utah)

So from an activist or farmer perspective, the CBA looks like:

“We took a modest cash/job sweetener without changing the underlying risks we’ve been fighting in court.”

That’s the core of the “you sold us out” framing.

3. How Hatt’s side of the table likely saw it

You can also read the same mechanics in the opposite direction: as a mayor trying to claw something tangible out of a process he had limited leverage over.

3.1 Bargaining power asymmetry

Look at the scale gap:

- A1/Anson/Blackstone: ASX-listed company with multiple large lithium projects, global partners (Koch, POSCO) and heavy state/federal interest in “critical minerals.”

- State level:

- State engineer and Division of Water Rights controlling the key water decision. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- SITLA/Trust Lands and federal agencies over land.

- Green River:

- ~850 people, General Fund revenue ≈ $2.0M/year. (Revize)

Most of the real “yes/no” levers on the project sit above the city: water rights, land leasing, higher-level permits.

That leaves a mayor with:

- Local zoning control,

- Political endorsement (or opposition),

- Some ability to shape public narrative, and

- The power to sign (or refuse) a CBA.

In that context, the CBA is basically the only instrument where he can extract:

- A defined annual cash flow,

- Jobs and training commitments,

- Transparency and reporting requirements.

You can see the “only card he had” logic:

“If the state and feds are already inclined to push this project through, we either get a signed CBA or we get nothing.”

3.2 How the CBA maps onto the city’s fiscal situation

Given that the General Fund is roughly $2.03M, a $100k/year dedicated stream that can be spent on:

- Sewer and wastewater upgrades,

- Emergency services,

- Community facilities,

is not trivial. (Revize)

For a town constantly juggling:

- Underfunded EMS,

- Aging infrastructure,

- Limited tax base,

a recurring 5% boost tied to one industrial anchor is something you can sell as a real, stabilizing win, especially if the alternative is “the project probably goes ahead anyway, and we get no dedicated pot at all.”

3.3 Community split: petition vs lawsuits

The A1 newsletter highlights that more than 120 residents signed a petition in favor of the project, roughly 15% of the entire population.

At the same time:

- Great Basin Water Network, Living Rivers, and local water users have been litigating hard against the water permit. (Great Basin Water Network)

So Hatt was operating in a triangle:

- A visible bloc of residents and businesses wanting the jobs and money.

- A sophisticated water/environment coalition warning of serious long-term risks.

- A state/federal apparatus eager for U.S. lithium and inclined to view the project favorably.

The CBA, from his chair, is the bridge between (1) and (3) with a nod toward (2) via transparency provisions—without actually derailing the project.

4. So was he “selling out” or playing his only card?

If you map the mechanics to perception, two clean narratives emerge.

4.1 The “selling out” narrative

Critics point to:

- Lowball cash: $100k/year vs other CBAs measured in the tens of millions, with no escalation formula publicly visible. (Human Rights Watch)

- No direct legal rights for residents:

- The “no third-party beneficiaries” language means only the city and company can enforce the deal. (River Simulator)

- Alignment with A1 during unresolved environmental fights:

- While GBWN and others are suing to block the water permit, the city signs on to “streamlined permitting and coordination.” (Great Basin Water Network)

- Speculative upside, real downside:

- Jobs and cash only materialize if the plant is built and profitable.

- Water and contamination risks, if they materialize, are long-term and structurally hard to reverse.

In that frame, the CBA looks like:

A modest PR-friendly agreement that gives A1 a “community support” talking point and a cooperative city hall, in exchange for what critics see as undervalued benefits and no real leverage on the underlying risks.

4.2 The “only card he had” narrative

Supporters and more pragmatic locals can point to the same document and argue the opposite:

- State and federal actors control the big levers; Green River cannot realistically veto a project of this strategic importance once the water and land boxes are ticked.

- The CBA:

- Forces A1 to put real numbers on the table (55+ jobs, $100k/year, school pipelines, quarterly meetings).

- Creates a formal expectation of transparency and ongoing public interface instead of leaving everything to state agencies and corporate press releases.

- Is structured so that elected officials, not an external foundation, control the money, preserving local democratic control over how benefits are used.

And crucially:

- For a city with a small tax base and a ~$2M General Fund, a 5% annual recurring revenue stream, earmarked for core infrastructure and emergency services, is non-trivial—especially if the counterfactual is: “the plant still comes, but with no dedicated community fund at all.” (Revize)

In that reading, the CBA is not a masterstroke, but it’s:

A constrained rural mayor using one of the few levers he actually controls to squeeze out jobs, cash, and public-facing conditions from a project largely driven by state, federal, and corporate forces.

4.3 What the CBA mechanics tell you about the power struggle

The technical details of the CBA actually confirm the broader power map you asked about earlier:

- Water and environmental risk live entirely in the hands of:

- State engineer,

- Courts,

- Federal land/water agencies, and

- The A1/Anson/Blackstone corporate structure. (The Salt Lake Tribune)

- Economic sweeteners and local optics live in:

- The CBA (Hatt and the council’s turf),

- A1’s petition drives and PR, and

- Local civic institutions (schools, EMS, infrastructure).

The CBA mechanics show Hatt operating at the edge of his formal power—trying to translate an externally driven lithium project into:

- A defined revenue stream,

- A local jobs/training pipeline,

- A procedural say over spending,

while leaving the deeper structural fights (water, aquifer, climate risk) to litigants and regulators he couldn’t directly control.

Whether that feels, to you, like “selling out” or “the only card he had” depends on which part you weight more heavily: the risk side that the CBA doesn’t touch, or the tangible concessions it actually nails down.